On Wednesday, neither of us felt like canoeing, although we had discussed a Vermilion River adventure. Sometime the day before, while passing through Buyck, we had stopped at the river to check out the water access. There, across the road from the VRT (Vermilion River Tavern), was a shabby golf course, on which stood an old barn where they kept the golf carts. On its north side, facing the river, hung an ancient Grain Belt sign, at least as old as the sacred bottlecap sign on the Mississippi in downtown Minneapolis. This sign was streaked with a gorgeous patina of rust.

Today, our first order of business was to call my mom to let her know we were definitely coming home the next day. My dad didn't want to drive to Orr again, because we had made the twenty mile drive every day we had been there. We got on the road and watched our phones for a signal. Funny enough, we got absolutely nothing until we reached the city limits of Orr. My dad made the call while I heeded nature's call inside the gas station.

We then parked in front of the on/off-sale liquor store/tavern to take care our second order of business: buying beer. I think we had about ten cans left for our last night, but when my dad had opened the cooler that morning, he became worried.

Since I had forgotten my ID, I stayed in the car, just to make it easier. My dad entered the building, and soon afterward, a man stepped out of a large black pickup next to me. He had a big, blond, Hogan mustache, and a long, greasy, curly mullet. He was quite a specimen of man, and he, too, entered the tavern.

While they were inside, I checked my messages from the past few days. There was a message from my friend Sho, who said that he and my other Rambo-watching buds had been playing music together, and were trying to book a show. Their name: Rambro!

My dad came out of the shop empty-handed. The other man also came out, they exchanged words, and my dad got in the car. He shook his head in disbelief. "You won't believe what just happened," he said. "So their computer was down. And the girl working was really stupid. I had my twelve-pack of Miller High Life up at the counter, and she said we can't make the exchange!"

"You couldn't just just give her the cash, and she'd ring it up later?" I asked.

"I guess not!" He sighed loudly. "So I turned around and was putting the beer back in the cooler, when that guy walked in. He must have thought my card didn't go through or something. And immediately, he said, 'Bring that back up here. I'll pay for it.'"

"Whoa!" I exclaimed.

"And at first, I brought it back. I thought maybe he was a local, and he knew how to handle these things. But when he found out the situation, even he couldn't do anything."

My dad was visibly touched by the man's kindness. The guy hadn't hesitated one instant, probably because he'd been on the opposite side of that situation before. He would not let my dad go without beer. What a man!

After getting our beer at the Sportsman's Last Chance in Buyck, we wanted to take a long hike, and decided to start in our campground at the Echo Lake Trail. It headed east from the main loop, beginning right next to the self-registration station.

We walked a ways through the woods, and the trail opened up onto a rocky outcropping with jack pines and a few blueberry plants with ripe berries. We enjoyed some while we paused to enjoy the spot. Continuing on, the trail led through the woods and onto more outcroppings. On these, the trail, worn into the soil in the woods, was invisible, but was marked by cairns someone had piled.

It was another beautiful, sunny day. Eventually, we emerged from the woods a final time, onto a huge expanse of rock and jack pines, from which a murder of crows took off. The rock face overlooked an immense valley of birch trees. And all around us grew ripe blueberries! I told my dad I wanted to go back to camp to get a tupperware to fill up, since blueberries are like seven dollars a pound in the store, and here they were, freely growing. He offered his quart-sized nalgene bottle to fill up, and this we began doing with determination.

A big handful contained about fifty of these smallish berries. We moved forward as we harvested, leaving countless missed berries, plus the underripe ones on each plant. Someone could do this again in a few days.

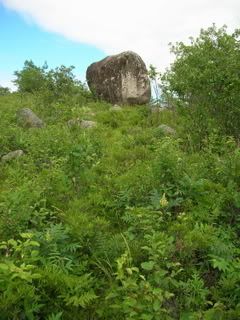

As we neared the top of a hill, we saw a giant boulder, twelve feet wide, just sitting at the summit like someone had placed it there.

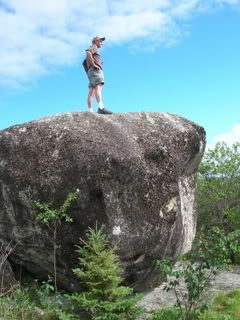

It was the highest point in the area. A cairn-builder had erected steps up to the climbable edges of the boulder, and I climbed up. Standing on top, I could see over the entire valley. The view was incredible.

Views from the boulder:

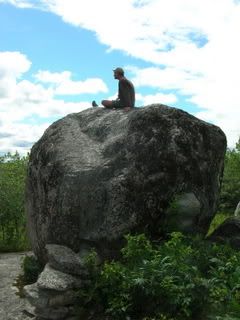

Then my dad took a turn up top.

When the bottle was filled with berries, I stowed it in my backpack. We could find no trail continuing on from the hillside, so we made our way back to camp.

That night we ate spaghetti dinner. As he had every other night that week, my dad took one last beer into the tent with him. There he read short stories by flashlight, and I would invariably find him asleep with his eyeglasses on his chest.

(28 June)

In the morning, we ate breakfast, struck camp, and said goodbye to Echo Lake.

A few hours down the road, in Hibbing, we went to SuperOne Foods again to get more of that ARCO coffee. While I waited for my dad to exit the bathroom, I overheard a checkout girl say she was going camping that weekend, at Echo Lake! Was this a crazy coincidence, or was it really that popular? It is an exquisite place to camp.

We got to the coffee aisle, and the entire ARCO display was gone! Not a trace remained. It must have been so cheap because they were discontinuing it. ARCO's new packaging had its own spot, and was regular coffee price. Shucks! We bought some snacks and hit the road.

Later, I directed us to the Aitkin County park with the aquifer. My dad was really into these side adventures, and said that he learns so much when we are together. The same is true for me. This had been the best father-son camping trip I'd ever experienced. It was different than any other because I was grown up. My dad had taught me most of what I know about camping, but on this trip, because he was really on vacation from his grueling academic duties, I naturally assumed leadership much of the time. The roles I knew from childhood were reversed. Maybe he was testing me.

My Dad.

My Dad.